On the 4th of August in the year 1578, the Battle of Ksar el Kebir was fought between the Sultan of Morocco Abu Abd al-Malik and the invading “crusader” expeditionary army led by the Portuguese King Sebastian I (b.1554-1578). One of the largest battles fought in North Africa in pre-modern times, 1400-1700, the battle is most famous for causing the death of the twenty-four year old Sebastian who was killed in one of the last great battles of the 16th century. In Portuguese this epic confrontation is called the Battle of Alcácer Quibir and is also popularly referred to as ‘The Battle of the Three Kings’ because three rulers fought and died in the battle and yet another would be crowned following the battle’s conclusion.

A prominent theme when examining the bellicose attitude taken towards Morocco by the Portuguese and the Spanish in the 15th and 16th centuries can be traced to the antiquated crusader ideals of the early middle ages. Coupled with global trade, through several notable explorers and navigators including Pedro Álvares Cabral (b.1467-1520), who as an admiral led a small fleet of ships which first discovered Brazil in South America and which later fought Muslim traders in India, bombarding their forts and later seizing Muslim ships at sea from 1499-1501, the Portuguese were an exploration and conquest based empire at the turn of the 15th century. They were the first true imperial power in this sense.

In terms of a chronological history the most important early events leading to greater Portuguese-Muslim conflict in northern Africa begin with the end of the Portuguese Reconquista with the conquest of Faro in 1250 by King Afonso III (b.1210-1279). Throughout the medieval age the Kingdom of Portugal and the Algarves would be at war with the Castilian kings whilst vigorously exploring West Africa and Northern Africa. In 1415, the year of the Battle of Agincourt, the Portuguese captured Ceuta in Morocco. They later settled the Azores islands and attempted to colonize the Canary islands in the year 1424 where they came face-to-face with the ‘Stone Age’ Guanche people of the islands. The Spanish would later claim the Canarys and would have to fight to take them from the Guanche kings following the capture of Grenada in 1492 (signaling the conclusion of the Granada War, 1482-1492) and the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494.

As early as 1437, Portugal had attacked the Sultanate of Morocco besieging and attempting to annex the city of Tangier. Under King Afonso V (b.1432-1481) known as the ‘African’ for his conquests (and attempted conquests) in Northern Africa, the Kingdom of Portugal and the Algarves would conquer numerous Moroccan enclaves and exclaves including Tangier and Casablanca between 1458-1476. In the early to mid 1500’s trading posts, forts, and even castles were erected throughout coastal India and Africa following on the heels of the conquest of Goa by Afonso de Albuquerque (b.1453-1515) in 1510, creating the Portuguese Indian Ocean empire.

Tutored by Jesuit confessors he learned to read and write and to speak the languages of the Iberian Peninsula. Portuguese knights taught him how to ride, joust, fight with a sword, and how to dress for battle (or how to stand uncomfortably and be dressed by pages and squires). He was a bright but impulsive young boy who was very fond of military pursuits. Evidence suggests that the young prince was molested by one of his Jesuit tutors from 1560-1566, a debauched missionary named Camara who was dismissed after the young prince became infected with a mysterious sexually transmitted disease around the age of twelve. Most likely gonorrhea, it would cause the king pain and great discomfort for the rest of his short life.

It was most likely the reason behind his notorious unwillingness to marry or to sire an heir. Beside the tragedy of abuse at the hands of this one Jesuit priest, the Jesuit order and perhaps his abuse instilled a great desire in the young king to conquer Morocco and to thereby win glory for Portugal and God. Perhaps years before he reached his majority in 1568 at the age of fourteen he had dreamt of one day riding at the head of a great Iberian crusader army to smite the heathen Sultanate of Morocco and to conquer North Africa. The pious young king was truly obsessed with succeeding where his great medieval and early 16th century predecessors had failed.

His chance came in 1576 when the ruling sultan Abdallah Mohammed II was dethroned in favor of Abd al-Malik referred to also as Mulay Abdelmalek, the son of Sultan Mohammed ash-Sheikh. The long ruling Saadi dynasty had been plagued by usurpations of power, civil war, and generational inter-tribal warfare between Sufi chieftains. The dethroned Sultan Abdallah Mohammed II fled to Portugal following his usurpation where he sought the aid and favor of King Sebastian and his court. Sultan Mohammed II wanted the kings’ of Spain and Portugal's help in defeating his Turkish supported rival, offering territory to Sebastian should he help him reclaim his sultanate.

Sebastian tried and failed to gain the support and the much needed manpower of his uncle King Philip II of Spain (b.1527-1598) during the Christmas celebrations of December and into January of 1577-1578. Though Philip originally pledged aid he ultimately reneged on the promise and sent only 500 unarmed Castilian volunteers, no doubt motivated by opportunities for wealth and adventure. His continental commitments to the Low Countries made intervention by Spanish forces impossible according to the King.

The Portuguese expeditionary army was some 15,000-20,000 strong whilst mustering to embark from Lisbon in the spring of 1578. Close to 7,000-8,000 of these fighting men were foreign troops and mercenaries including Germans, Castilians, and Italians. A Papal infantry contingent led by the Englishmen Sir Thomas Stukeley (b.1520-1578), a veteran of the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, was diverted from an invasion of Ireland to sail with Sebastian's fleet in late June of 1578. The core of this army however was either Portuguese or Moorish. Along with their Moorish allies the Portuguese had some 23,000-25,00 soldiers in arms whilst in Morocco. Both the most powerful dukes and petty knights of the Portuguese nobility unanimously supported the kings’ crusade as did the gentry and peasant classes, the noble contingent numbering some 8,000-9,000 men and non-combat attendants.

Sebastian's army landed at Asilah (Arzila) a small coastal fortress city 20 miles or so south of Tangier in early July 1578. At Arzila the Portuguese, their Moorish allies, and the substantial mercenary division languished for nearly a month thereafter eating their supplies and becoming disenchanted with the stalled crusade. Meanwhile their Moroccan enemies were mobilizing in the tens of thousands once the call for jihad spread after it had declared by their sultan Abd al-Malik I. Sebastian would have been surrounded by chivalry on his march south to Ksar el Kebir after landing in Northern Africa. Over 2,000 of his force were comprised of the (mostly) elite Aventuros and Encubertados, heavily armored gentlemen of war who could afford to outfit themselves and their household retainers on campaign in the kings army. Their primary desire was to win favor, titles, honors, and glory for Portugal and their king in battle. It was an opulent march, the Portuguese lords and dukes traveling fully provisioned with all of their comforts.

One source which Plummer cites remarks on how the nobility were ill suited for the rigors of a campaign in enemy country. "Instead of sharpening their weapons, they embroider their clothes. Instead of corselets, they outfit themselves with doublets adorned with silk and gold. They load themselves with sweets and fine foods, rather than biscuits and water.” One of the nobles was the ten year old Teodósio (b.1568-1630) the Duke of Barcellos and heir to the historic line of the Dukes of Braganza who brought a massive retinue matching the kings’ own.

Awaiting them around 6 miles south of Ksar el Kebir was the army of Sultan Abd al-Malik I and his brother-general, Moulay Ahmed (b.1549-1603) the emir Fez. They commanded an impressive host as large as 50,000-70,000 fighting men though both of these estimates might still be inaccurate. Sebastian and his army may have lost the battle beforehand in moving so quickly for Ksar el Kebir, his men already tired and hungry, they were made to cross the fast flowing Makhazen river to attack the Moroccan sultan at next daylight instead of building a fortified encampment in a more defensively sound location with the river in front of them. They were low on supplies and totally unaware that they were marching towards an army that outnumbered them almost 3 to 1. Moulay Ahmed commanded some 20,000 cavalry and 5,000 arquebusiers (matchlock musket armed infantry) alone.

The Portuguese Aventuros and Encubertados sundered forth first on King Sebastian's command, charging hard into the crescent of the Moroccan lines. This initial charge was effective as Plummer notes the defending “[Moroccan] arquebusiers volleyed and buckled [the encubertados] lines, but the slowness of reloading allowed the Portuguese to close. The pike then did its work, driving the Moslem front ranks back and throwing their center into confusion.” Sebastian’s Portuguese infantrymen and mercenaries marched forward only to be trampled by the retreating heavy cavalry and then engulfed by the Moroccan infantry wielding their scimitars with fury.

Although the Aventuros fought furiously reaching the Moroccan guns they were ultimately repelled. Jorge de Lencastre the Duke of Aviero launched a furious assault in an attempt to save the Portuguese and mercenary center but to no avail. The routed Portuguese mercenaries and their Moorish allies were later cut to pieces by the cavalry of Ahmad al-Mansur now sultan of Morocco but unaware of the death of his brother and predecessor until the tide of the battle had turned in their favor. Apparently the Portuguese noble infantry was beaten back and but not yet routed until a minor nobleman yelled that they should retreat despite previously holding a tactical edge in the offensive.

A classic Portuguese source claims that the king left his retainers to fight in the advance charge, noting that Sebastian “fought like a lion to save it from annihilation. The young king battled with fanatical courage, rushing here and there, bringing reinforcements and leading cavalry charges in a futile attempt to hold the square together-wounded in the arm, with three horses shot from beneath him, Don Sebastian was relentless. It was said that he killed as many of the enemy as any man in the [Portuguese] army that day.”

Around 8,000 of Sebastian's army were killed in the Battle of Ksar el Kebir and close to 15,000-16,000 were wounded and/or captured. Almost every noble family suffered a slain family member and some were entirely extinguished following the conclusion to the battle. The Moroccans lost approximately 6,000 killed or severely wounded. Of the survivors on the Portuguese side who were later ransomed by Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur were the young Duke of Barcellos, wounded in the fray despite Sebastian's orders that he be placed far from the battlefield, António the prior of Crato (b.1531-1595), an influential man who was related to Sebastian’s grandfather King John III and who would later fight as a pretender to keep the Portuguese crown out of Spanish hands until the year 1583, and Don Juan da Silva, the Spanish ambassador to Sebastian's court.

King Philip II’s own words to Don da Silva before the campaign proved eerily prophetic, “if he succeeds, we shall have a fine nephew, if he fails, a fine kingdom". Following the War of the Portuguese Succession in 1580-1583 which had begun with the death of Cardinal Henry the successor and former regent of King Sebastian, Philip would become the King of Portugal as Philip I, joining those two nations in a Spanish (Habsburg) dominated Iberian union until 1640. It would be John IV (b.1604-1656), the son of the young noble survivor of Ksar el Kebir, the Duke of Braganza, who would restore Portuguese sovereignty following the Restoration in 1640.

Heroic contemporary painting and portrait of King Sebastian I (b.1554-1578), depicting the young crusader king, killed leading at the Battle of Ksar El Kebir, August 4th, 1578.

A prominent theme when examining the bellicose attitude taken towards Morocco by the Portuguese and the Spanish in the 15th and 16th centuries can be traced to the antiquated crusader ideals of the early middle ages. Coupled with global trade, through several notable explorers and navigators including Pedro Álvares Cabral (b.1467-1520), who as an admiral led a small fleet of ships which first discovered Brazil in South America and which later fought Muslim traders in India, bombarding their forts and later seizing Muslim ships at sea from 1499-1501, the Portuguese were an exploration and conquest based empire at the turn of the 15th century. They were the first true imperial power in this sense.

Portuguese warfare and exploration before & during the reign of King Sebastian, 1494-1566

In terms of a chronological history the most important early events leading to greater Portuguese-Muslim conflict in northern Africa begin with the end of the Portuguese Reconquista with the conquest of Faro in 1250 by King Afonso III (b.1210-1279). Throughout the medieval age the Kingdom of Portugal and the Algarves would be at war with the Castilian kings whilst vigorously exploring West Africa and Northern Africa. In 1415, the year of the Battle of Agincourt, the Portuguese captured Ceuta in Morocco. They later settled the Azores islands and attempted to colonize the Canary islands in the year 1424 where they came face-to-face with the ‘Stone Age’ Guanche people of the islands. The Spanish would later claim the Canarys and would have to fight to take them from the Guanche kings following the capture of Grenada in 1492 (signaling the conclusion of the Granada War, 1482-1492) and the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494.

As early as 1437, Portugal had attacked the Sultanate of Morocco besieging and attempting to annex the city of Tangier. Under King Afonso V (b.1432-1481) known as the ‘African’ for his conquests (and attempted conquests) in Northern Africa, the Kingdom of Portugal and the Algarves would conquer numerous Moroccan enclaves and exclaves including Tangier and Casablanca between 1458-1476. In the early to mid 1500’s trading posts, forts, and even castles were erected throughout coastal India and Africa following on the heels of the conquest of Goa by Afonso de Albuquerque (b.1453-1515) in 1510, creating the Portuguese Indian Ocean empire.

Beginning in the 1530’s and 1540’s the Portuguese aided the Christian kings of Ethiopia in their battles with the Ottoman Empire in East Africa. Jesuit missionaries and Portuguese merchant sailors first went ashore to Japan in 1542 during the Sengoku or Warring States period. They established trading hubs and settlements in Macau and Malacca (Malaysia) with the conquered and brutalized regions claimed by Afonso de Albuquerque ‘the Great’. Under King Sebastian an armed and trained militia was established in Goa to deal with the threat of revolt or Muslim incursion from 1566-1570. Outposts were also built in Angola and throughout East Africa as well.

In all of these endeavors a combination of factors propelled the Portuguese to wage war. Principle among them were financial concerns (the money to be made through colonization and exploration of the ‘New World’), winning glory in battle, converting non-believers to Christianity (and the before mentioned antagonistic attitude towards the Muslims), and out of a pure sense of loyalty to the King of Portugal (patriotism).

Unquestionably the most intriguing of the Three Kings who fought at the Battle Ksar el Kebir, King Sebastian became King of Portugal at the age of three following the death of his grandfather, King John III in the year 1557. His father João Manuel the Prince of Portugal had died in 1554. The young Prince Sebastian was looked after by his grandmother and regent Catherine of Austria from 1557-1562. From 1562-1568 his uncle Henrique (Henry) a Roman Catholic Cardinal, served as his regent. Though his grandmother was a devout Roman Catholic his uncle and other patriotic (anti-Castilian) Portuguese court members ensured that the young prince would be raised a Jesuit.

In all of these endeavors a combination of factors propelled the Portuguese to wage war. Principle among them were financial concerns (the money to be made through colonization and exploration of the ‘New World’), winning glory in battle, converting non-believers to Christianity (and the before mentioned antagonistic attitude towards the Muslims), and out of a pure sense of loyalty to the King of Portugal (patriotism).

King Sebastian & Abdallah Mohammed II versus Sultan Abd al-Malik

Unquestionably the most intriguing of the Three Kings who fought at the Battle Ksar el Kebir, King Sebastian became King of Portugal at the age of three following the death of his grandfather, King John III in the year 1557. His father João Manuel the Prince of Portugal had died in 1554. The young Prince Sebastian was looked after by his grandmother and regent Catherine of Austria from 1557-1562. From 1562-1568 his uncle Henrique (Henry) a Roman Catholic Cardinal, served as his regent. Though his grandmother was a devout Roman Catholic his uncle and other patriotic (anti-Castilian) Portuguese court members ensured that the young prince would be raised a Jesuit.

Dom Sebastian as a teenager

Tutored by Jesuit confessors he learned to read and write and to speak the languages of the Iberian Peninsula. Portuguese knights taught him how to ride, joust, fight with a sword, and how to dress for battle (or how to stand uncomfortably and be dressed by pages and squires). He was a bright but impulsive young boy who was very fond of military pursuits. Evidence suggests that the young prince was molested by one of his Jesuit tutors from 1560-1566, a debauched missionary named Camara who was dismissed after the young prince became infected with a mysterious sexually transmitted disease around the age of twelve. Most likely gonorrhea, it would cause the king pain and great discomfort for the rest of his short life.

It was most likely the reason behind his notorious unwillingness to marry or to sire an heir. Beside the tragedy of abuse at the hands of this one Jesuit priest, the Jesuit order and perhaps his abuse instilled a great desire in the young king to conquer Morocco and to thereby win glory for Portugal and God. Perhaps years before he reached his majority in 1568 at the age of fourteen he had dreamt of one day riding at the head of a great Iberian crusader army to smite the heathen Sultanate of Morocco and to conquer North Africa. The pious young king was truly obsessed with succeeding where his great medieval and early 16th century predecessors had failed.

His chance came in 1576 when the ruling sultan Abdallah Mohammed II was dethroned in favor of Abd al-Malik referred to also as Mulay Abdelmalek, the son of Sultan Mohammed ash-Sheikh. The long ruling Saadi dynasty had been plagued by usurpations of power, civil war, and generational inter-tribal warfare between Sufi chieftains. The dethroned Sultan Abdallah Mohammed II fled to Portugal following his usurpation where he sought the aid and favor of King Sebastian and his court. Sultan Mohammed II wanted the kings’ of Spain and Portugal's help in defeating his Turkish supported rival, offering territory to Sebastian should he help him reclaim his sultanate.

Sebastian tried and failed to gain the support and the much needed manpower of his uncle King Philip II of Spain (b.1527-1598) during the Christmas celebrations of December and into January of 1577-1578. Though Philip originally pledged aid he ultimately reneged on the promise and sent only 500 unarmed Castilian volunteers, no doubt motivated by opportunities for wealth and adventure. His continental commitments to the Low Countries made intervention by Spanish forces impossible according to the King.

Portrait of King Sebastian I as he would have looked nearer to August of 1578

Sebastian's army landed at Asilah (Arzila) a small coastal fortress city 20 miles or so south of Tangier in early July 1578. At Arzila the Portuguese, their Moorish allies, and the substantial mercenary division languished for nearly a month thereafter eating their supplies and becoming disenchanted with the stalled crusade. Meanwhile their Moroccan enemies were mobilizing in the tens of thousands once the call for jihad spread after it had declared by their sultan Abd al-Malik I. Sebastian would have been surrounded by chivalry on his march south to Ksar el Kebir after landing in Northern Africa. Over 2,000 of his force were comprised of the (mostly) elite Aventuros and Encubertados, heavily armored gentlemen of war who could afford to outfit themselves and their household retainers on campaign in the kings army. Their primary desire was to win favor, titles, honors, and glory for Portugal and their king in battle. It was an opulent march, the Portuguese lords and dukes traveling fully provisioned with all of their comforts.

One source which Plummer cites remarks on how the nobility were ill suited for the rigors of a campaign in enemy country. "Instead of sharpening their weapons, they embroider their clothes. Instead of corselets, they outfit themselves with doublets adorned with silk and gold. They load themselves with sweets and fine foods, rather than biscuits and water.” One of the nobles was the ten year old Teodósio (b.1568-1630) the Duke of Barcellos and heir to the historic line of the Dukes of Braganza who brought a massive retinue matching the kings’ own.

Teodosio II as a young man. He eldest son, John, would become King of Portugal in 1640

Moroccan cavalry riding to war depicted in the 17th century

The Battle of the Three Kings

King Sebastian ordered his troops forward in the early afternoon hours of August 4th. With his artillery pieces hauled into place the Portuguese allied armies made a general march forward towards the Moroccan lines of the Sultan and Moulay Ahmed. Under his personal standard and the sacred green banner of Islam, Sultan Abd al-Malik rode before his warriors, proclaiming that they should "Oppose him [King Sebastian] with your valor-for you fight in the most noble enterprise: That which prevents injury to your families, upholds liberty, conserves life, acquires honor, and, which, living or dying as it may be, leads to Paradise!" His men knew that their sultan spoke truthfully though they were unable to see that he was strapped to his horse unable to ride himself as he was nearly succumbing to the effects of plague or camp sickness. He would be dead before the battle was decided and his brother Moulay Ahmad would succeed him.Although the Aventuros fought furiously reaching the Moroccan guns they were ultimately repelled. Jorge de Lencastre the Duke of Aviero launched a furious assault in an attempt to save the Portuguese and mercenary center but to no avail. The routed Portuguese mercenaries and their Moorish allies were later cut to pieces by the cavalry of Ahmad al-Mansur now sultan of Morocco but unaware of the death of his brother and predecessor until the tide of the battle had turned in their favor. Apparently the Portuguese noble infantry was beaten back and but not yet routed until a minor nobleman yelled that they should retreat despite previously holding a tactical edge in the offensive.

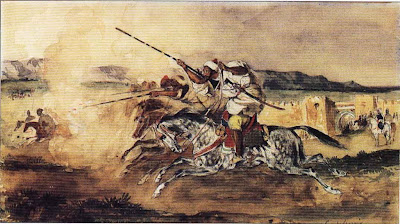

In the thick of the melee at Battle of Alcácer Quibir or Oued El Makhazeen (Moroccan)

Though this a highly exaggerated account drawn from a secondary period source who was not present at the battle, Sebastian did indeed fight bravely in the battle and was wounded at least once before his death. From primary sources we know that he was most likely amongst the less than 4,000 Portuguese, Germans, Castilians, and Italians commanded by the Duke of Aveiro and Sir Thomas Stukeley who made a last stand of sorts and who were among the very last to die. The Castilians fought to the death with daggers and were the last to be slain in this bloody melee.

Abdallah Mohammed fled the field in the rout and then perished when he was thrown from his horse and drowned in the Makhazen river. Most of his men on mounts likely escaped the greater carnage. The last remaining Portuguese and European men in arms were “cruelly” slaughtered when “a swarm of Arab irregulars who had lingered on the periphery of the battle, impatient to join the pillage that was now beginning, intervened to hasten the end. They fell on the exhausted, blood-soaked survivors and with their crude instruments clubbed and hacked them down.”

King Sebastian had charged to his death just minutes before, the twenty-four year old monarch lost in a mass of the enemy army. His body was never recovered which fueled popular myth in the aftermath of his death that he survived the battle and would return to march on Lisbon. Sultan Ahmad ‘al-Mansur’ earned his title “The Victorious” after the great victory and would reign until his death in 1603. He became a great conqueror and statesman known for annexing Touat in Algeria and for later sending an army under the eunuch general, Judar Pasha into Mali. Following the Battle of Tondibi in 1591, Judar Pasha sacked the great cities of Gao and Timbuktu which had been previously ruled by the prosperous Songhai Empire. Sultan al Mansur is also famous for sending an ambassador to the court of Queen Elizabeth I in the year 1600.

King Sebastian, center, in the thick of a charge during the battles' later stages

Abdallah Mohammed fled the field in the rout and then perished when he was thrown from his horse and drowned in the Makhazen river. Most of his men on mounts likely escaped the greater carnage. The last remaining Portuguese and European men in arms were “cruelly” slaughtered when “a swarm of Arab irregulars who had lingered on the periphery of the battle, impatient to join the pillage that was now beginning, intervened to hasten the end. They fell on the exhausted, blood-soaked survivors and with their crude instruments clubbed and hacked them down.”

King Sebastian had charged to his death just minutes before, the twenty-four year old monarch lost in a mass of the enemy army. His body was never recovered which fueled popular myth in the aftermath of his death that he survived the battle and would return to march on Lisbon. Sultan Ahmad ‘al-Mansur’ earned his title “The Victorious” after the great victory and would reign until his death in 1603. He became a great conqueror and statesman known for annexing Touat in Algeria and for later sending an army under the eunuch general, Judar Pasha into Mali. Following the Battle of Tondibi in 1591, Judar Pasha sacked the great cities of Gao and Timbuktu which had been previously ruled by the prosperous Songhai Empire. Sultan al Mansur is also famous for sending an ambassador to the court of Queen Elizabeth I in the year 1600.

Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur (r.1578-1603)

Around 8,000 of Sebastian's army were killed in the Battle of Ksar el Kebir and close to 15,000-16,000 were wounded and/or captured. Almost every noble family suffered a slain family member and some were entirely extinguished following the conclusion to the battle. The Moroccans lost approximately 6,000 killed or severely wounded. Of the survivors on the Portuguese side who were later ransomed by Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur were the young Duke of Barcellos, wounded in the fray despite Sebastian's orders that he be placed far from the battlefield, António the prior of Crato (b.1531-1595), an influential man who was related to Sebastian’s grandfather King John III and who would later fight as a pretender to keep the Portuguese crown out of Spanish hands until the year 1583, and Don Juan da Silva, the Spanish ambassador to Sebastian's court.

King Philip II’s own words to Don da Silva before the campaign proved eerily prophetic, “if he succeeds, we shall have a fine nephew, if he fails, a fine kingdom". Following the War of the Portuguese Succession in 1580-1583 which had begun with the death of Cardinal Henry the successor and former regent of King Sebastian, Philip would become the King of Portugal as Philip I, joining those two nations in a Spanish (Habsburg) dominated Iberian union until 1640. It would be John IV (b.1604-1656), the son of the young noble survivor of Ksar el Kebir, the Duke of Braganza, who would restore Portuguese sovereignty following the Restoration in 1640.

Suggested Further Reading

Johnson, Harold B. A Pedophile in the Palace: or The Sexual Abuse of King Sebastian of Portugal (1554-1578) and its Consequences. (University of Virginia).

Nicolle, David The Portuguese in the Age of Discovery c.1340-1665. Illustrated by Gerry & Sam Embleton (Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK 2012).

Plummer, Comer, US Army (Ret.) Apocalypse Then: The Battle of the Three Kings. (2008).